Dickson book reveals why U.S. was prepared to fight after Pearl Harbor

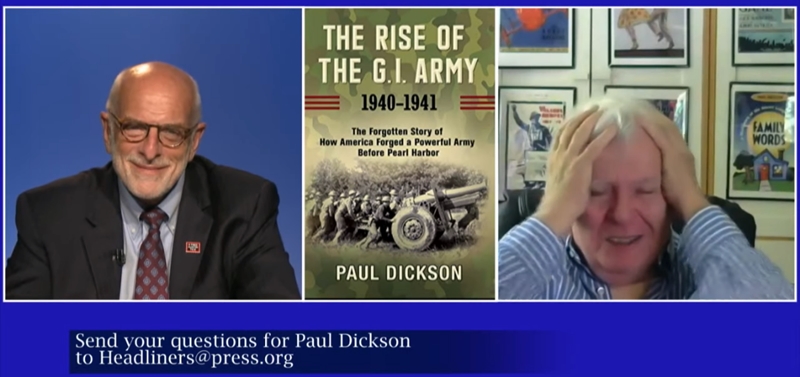

In his new book, "The Rise of the G.I. Army, 1940-1942: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl Harbor,” Paul Dickson sheds light on steps the U.S. took in the years preceding World War II to establish the army that withstood the century’s greatest conflict.

Speaking with Press Club President Michael Freedman during a virtual Book Rap conversation August 14, Dickson credited decisions by former U.S. Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall and implemented by some of the era’s most prominent figures, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, General George S. Patton and General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

There’s a good chance you learned in high school that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor prompted the U.S. to suddenly drop its isolationist tendencies and scrape together a massive army overnight. Dickson reveals this is only half the story.

"If we hadn’t built this army before Pearl Harbor, if we hadn’t developed this phenomenal officer corps, we would have been in terrible, terrible shape,” Dickson said, “The war could have gone on considerably longer and it would’ve cost a million more lives.”

“There was this huge prehistory [to Pearl Harbor] that nobody has really put together as a coherent whole," he added.

The most important step toward fortifying the Army, Dickson found, came in the fall of 1940, when a peacetime draft was declared and men from across the country and from all walks of life were suddenly summoned to military bases for basic training.

As Dickson tells it, there was surprisingly little grumbling, even though thousands were pulled from well-paying jobs and shoehorned into unfamiliar circumstances.

To highlight this, Dickson offered a tongue-in-cheek contrast to the present.

“Today, people are screaming about masks,” Dickson quipped. “Back then, [Americans] were told you have to go to war and we don’t even have a war started yet.”

After the initial draft, Marshall ordered a series of massive field exercises across the South to give the would-be servicemen a taste of what it’s like to operate as a unit.

According to Dickson, these sprawling mock battles didn’t just prepare the draftees, they also showcased some of the strengths they would have over those who fought in World War I — namely, a familiarity with cars.

“These guys had all grown up with cars, so the first time they saw a tank, the first time they saw a Jeep, the first time they saw an airplane, their first inclination was to dive under the hood,” Dickson shared.

“They had grown up with gas station roadmaps,” he added, noting that WWI battalions would often get lost since most servicemen had little experience with in-depth maps.

Drawing things back to the National Press Club, Dickson explained that these exercises, which ultimately drew in 890,000 men, did not go unnoticed by the era’s media giants.

CBS Radio, for instance, sent in 22 reporters and began covering the training as if it was a real war. The network even roped in silver screen icon Burgess Meredith to narrate the day-to-day operations and inject their broadcasts with a healthy dose of drama.

Much like the field trainings gave the draftees a chance to cut their teeth ahead of the war, Dickson suggested that they also shaped the iconic radio reporting that came out in the following years.

Dickson pointed to the impact the exercises had on one reporter in particular: Eric Sevareid, a colleague of legendary newsman Edward R. Murrow and a National Press Club fixture up until his death in 1992.

“Eric Sevareid watches these guys and realizes they really want to win,” Dickson recalled. “The night of Pearl Harbor, and he’s the one who makes the big announcement on CBS. He goes to bed that night and writes in his diary that he’s sleeping soundly. ‘I know we’re going to win.’”