Hear Club member Larry LeSueur describe his D-Day landing

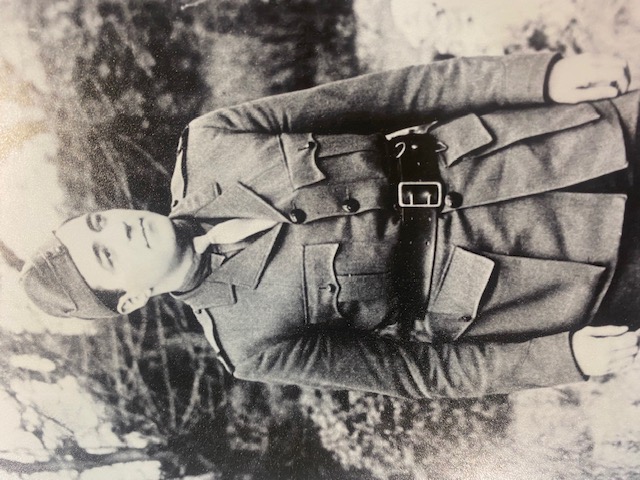

Eighty years ago on June 6 –- the day that will always be remembered in American history as D-Day -– a reporter by the name of Larry LeSueur landed at Utah Beach in the first wave, armed only with a typewriter.

LeSueur, who became a National Press Club member after World War II, was one of the elite CBS Radio reporters known as the Murrow Boys, working for Edward R. Murrow, who from the earliest days of the war invented broadcast news to get the stories back to radio listeners in the United States.

On the 80th anniversary of D-Day, long-time History and Heritage Team member Carol Bennett has unearthed the interview she did with LeSueur 40 years ago. She interviewed LeSueur for the University of Maryland’s Broadcast Pioneers’ Archive shortly before he returned to Normandy to report on the 40th anniversary of D-Day in 1984.

“I am pleased I was able to record it and to be here 40 years later to bring it to light again,” she said.

LeSueur was born in New York City in 1909, the son and grandson of journalists. His father was a foreign correspondent for the New York Tribune. His first reporting job after graduating from New York University was with United Press. In 1939, as World War II loomed, he went to England and asked Murrow for a job.

He reported the London Blitz with Murrow, and then was sent to the Soviet Union in 1941 as the Moscow correspondent and was in the midst of the Battle for Stalingrad that turned the tide of the war on the Eastern Front.

He was back in London in preparation for the D-Day landing. In his conversation with Bennett, he described the secrecy around the D-Day invasion, how he was “arrested” to be sequestered with other reporters heading for the invasion. He had volunteered to be the CBS reporter to land with the infantry, despite the extreme danger.

Along with the typewriter, he was supposed to carry a cumbersome wire recorder and a two-foot-long gasoline generator that weighed 50 pounds to power the recorder. That was just impossible, and he left them behind on the ship as he boarded the landing craft for the beach.

Leaving at night on June 3, he and the infantrymen bobbed around in the turbulent ocean as they awaited the storm to subside enough for Gen. Dwight Eisenhower to decide to launch the invasion at dawn on June 6, on what was known as H-Hour.

'It came as a shock...we, too, could die'

LeSueur’s craft landed at H-Hour plus 20 minutes after drifting about 10 miles from the designated landing site. He saw soldiers wounded around him as German artillery blasted the beach. He dragged some of the wounded to a shelter where they could get medical care. Most of the tanks with them sank with all aboard.

“It came as a shock to all of us to think that we, too, could die,” he said.

At dark on the first day, he wrote his first story on the typewriter in a farmhouse he found. He took it back to the beachhead and gave it to a Naval officer, asking that he get it onto one of the landing craft heading back to the fleet.

“My luck wasn’t very good, because the stories I filed for several days were simply lost,” he said.

Not until three or four days later was the army able to land a small generator in a trailer, he said. He said he was able to make his first broadcast about American landings on Utah Beach and get it back to England over the Channel, where the BBC then relayed it to the United States.

That was just the beginning as he moved inland with the American troops, traveling back and forth to the beach where his transmitter was still in range. He stayed with the troops as they fought their way over three months to reach Paris –- which was only about a two-hour drive from Normandy.

He was with a French tank division as it liberated Paris. Arriving before the American military censors, he reported from a secret French underground radio transmitter, just hoping that the BBC in London would pick it up. “Paris is the happiest city in the world tonight,” he reported. “All Paris is dancing in the streets.”

For this, military authorities punished him for not having censors approve his broadcast by lifting his press credentials for 30 days.

As he told Bennett, “It was a great pleasure to me to do the first broadcast from Paris,” because he had been in Paris in 1940 when the Germans came in.

To hear the interview, click here: