National Press Club Headliners Book Rap explores tapping Soviet secrets in 1950s Berlin

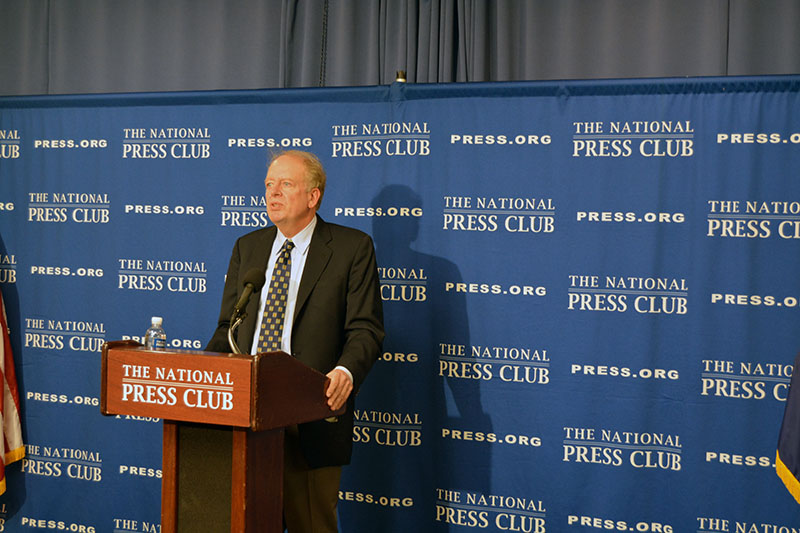

Steve Vogel raps about his book, "Betrayal in Berlin: The True Story of the Cold War’s Most Audacious Espionage Operation," at an Oct. 10 National Press Club event. Photos: Joseph Luchok

The tunnel project in Berlin was hellishly hot, dirty and claustrophobic — and, most importantly, top secret. Three teams, each with 20 men, began digging in November 1954 to tap into buried Soviet landlines, one of the most dramatic and daring American intelligence operations in history.

Steve Vogel, too, had to dig deep for nearly five years to unearth the tale and piece together the cast of characters for his recently published book, “Betrayal in Berlin: The True Story of the Cold War’s Most Audacious Espionage Operation.” Vogel, an author and veteran journalist for The Washington Post, stopped by the National Press Club on Oct. 10 to share the inside story.

The book, Vogel said, revisited his scattered connections to Germany and the intelligence community.

Vogel was born and grew up in Berlin, while his father was stationed there as a CIA case officer — though the two never discussed the job. Then, in 1989, Vogel traveled back to Berlin, planning to freelance for a few months. After the fall of the Berlin Wall that year, he ended up staying for five years to cover the aftermath.

It was not until 2014, when he attended a seminar on spy tactics, hosted by the U.S. Army War College and Dickinson College, that Vogel learned more about the Americans’ tunnel into East Berlin.

“I was just really taken by the story,” Vogel said. “I knew the bare bones of it. It just seemed to me that there was more to tell.”

The grueling physical work was a reminder of how far intelligence-gathering techniques have advanced, he explained, as today’s satellite surveillance and digital tools render tunnels obsolete. It was also a sign of just how desperate for information American officials had become in the early years of the Cold War. The Soviets had developed nuclear weapons quicker than many expected, he said, and there were fears of a “nuclear Pearl Harbor” attack.

The idea for a half-mile tunnel that could tap into Soviet telephone landlines was hatched in part by CIA field operator Bill Harvey, a brash heavy drinker from Indiana who insisted on always carrying a half-dozen weapons. Harvey worked with British intelligence officials, who had built much smaller tunnels in Vienna.

Berlin “would be the place where they really hit the mother lode,” Vogel said. Indeed, once complete, Washington scrambled to parse the deluge of calls, which picked up everything from top military officers and KGB agents to lowly clerks and aides.

Vogel said he found “a surprising number” of people who were involved with the tunnel and still alive. The real treasure trove, he said, was an archive of interviews, letters and other research donated by Bayard Stockton, an author who wrote a biography of Harvey.

Does Vogel see another book in all he discovered in his research?

“I wouldn’t rule anything out,” he said with a laugh.