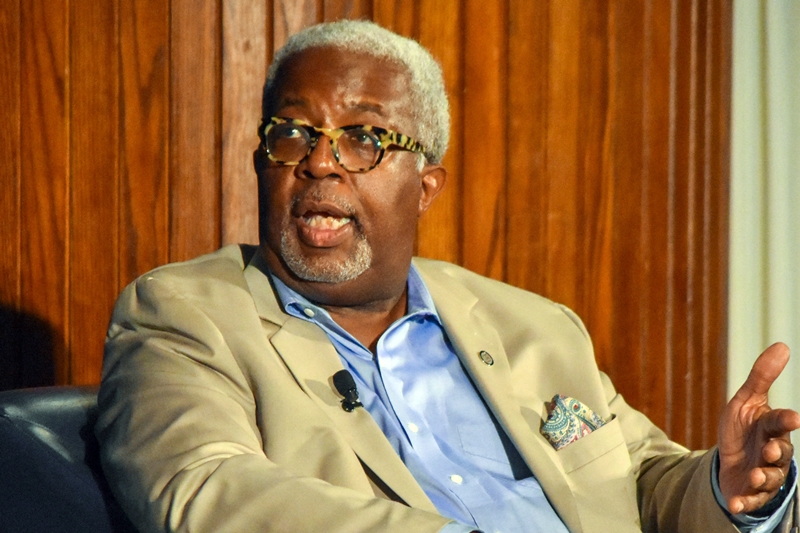

Journalists Sam Fulwood, dean of American University's School of Communication; Elahe Izadi, media reporter for The Washington Post; and Terence Samuel, vice president of news at NPR, addressed the persistent problem of misinformation and the erosion of public trust in a discussion with PBS Public Editor Ricardo Sandoval-Palos at a joint PBS/National Press Club event on June 30.