'The power of journalism to educate, to inform': Gilbert M. Grosvenor reflects on 50 years at National Geographic

With tales of derring-do as a roving international writer, coupled with insights of developing one of the world’s leading magazines, Gilbert M. Grosvenor entertained more than a hundred people in the National Press Club ballroom Jan. 27 recounting his 50 years with the National Geographic Society.

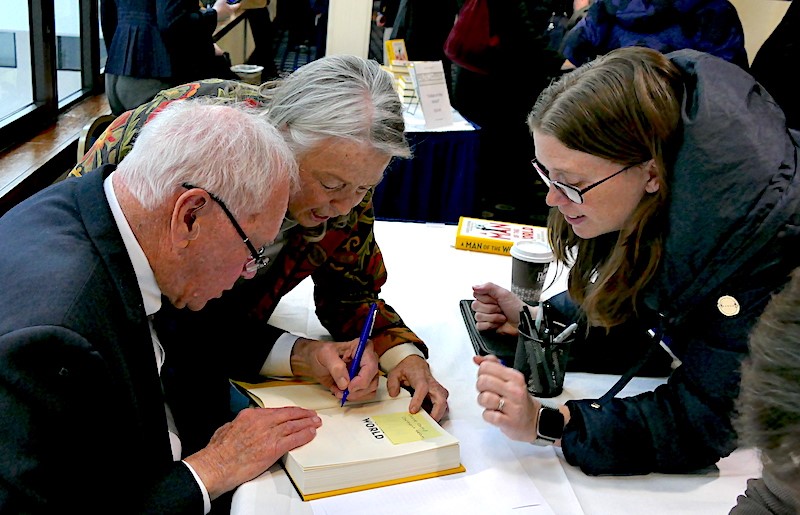

At 91 years old and nearly blind, Gilbert Grosvenor had no trouble captivating his audience as his younger brother, Edwin Grosvenor, editor of American Heritage Magazine, threw him question after question. Ed Grosvenor is a member of the Club’s History and Heritage Committee, which sponsored the event.

The Grosvenor family’s involvement in the Club goes back more than 100 years. Gil’s grandfather, Gilbert H. Grosvenor, was a member of the Club at least since 1914, and probably as far back at 1909, a year after the Club was founded. Gil Grosvenor was photographed in 1956 voting in a Club election with his father and grandfather.

Grosvenor recently published A Man of the World: My Life at National Geographic, which describes feats of exploration, from Jane Goodall's field studies to the successful hunt for the Titanic. Offering a rare portrait of one of the world's most iconic media empires, this revealing autobiography makes an impassioned argument to know―and care for―our planet.

When he was in college, Grosvenor intended to go into medicine. But that changed after he wrote an article for National Geographic about volunteering after the terrible 1953 flood in the Netherlands. “I discovered that few people knew about Netherlands, and the article had a real impact,” he said. “I realized the power of journalism to educate, to inform.”

Grosvenor recalled how his grandfather had taken over the magazine as its first employee when it had only 900 members. Known as “GHG,” he edited it for 50 years and built the Society to a worldwide organization with over a million members.

But by the 1950s, the magazine needed a shot in the arm. Gil’s father, Melville Grosvenor, became editor, added new staff and launched television, books, and educational media. He pointed out that when the magazine faced a shortfall, “MBG” gained more revenue from new products rather than cutting costs and staff.

Drawing from his rich career, Grosvenor told a number of stories about his challenges as a writer. When he interviewed Marshall Tito of Yugoslavia, who asked about his cameras, Grosvenor reached to take a telephoto lens with gunstock out of his case, but was immediately pinned to the ground by two bodyguards who came out from behind a hedge.

He also recalled some harrowing moments. When he was covering the start of the Tall Ships race leaving Bermuda, the engine of his chartered plane conked out. The pilot yelled, “Mayday,” and told the two passengers to put on their lifejackets. Grosvenor looked at his photographer, Joe Scherschel, and saw he was taping his film to his lifejacket instead of putting it on himself. “That was when I learned the difference between an editor and a photographer,” he said.

Diving under Arctic Shelf

And he told the story about diving under the Arctic ice shelf. In the early part of the 20th century, National Geographic had helped fund Adm. Robert E. Peary’s quest to be the first person to reach the North Pole, he said.

“I knew I wanted to do one thing: I wanted to walk upside down under the ice, and that wasn’t easy,” he said. “I had gotten a postcard from my father saying he had flown over the footsteps of Peary. So, I wanted to do one better. I sent him a postcard saying I had walked beneath the footsteps of Robert E. Peary."

Gilbert M. Grosvenor left his own mark on the Society. As staff photographer, editor in chief and then president of the organization, Grosvenor oversaw more diversification and the flagship magazine reached a peak circulation of nearly 11 million. He also credited the Society’s success to the hard work and loyalty of its “family.” Many of the former staff were in attendance.

For Grosvenor, running National Geographic wasn’t just a job. It was a legacy, motivated by a passion not just to leave the world a better place, but also to motivate others to do so, too.