Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist discusses how his art improved a life, at NPC book event

At age 29, Jackie Wallace left the Los Angeles Rams after playing in two Super Bowls over six seasons in the National Football League. Armed with a college degree, Wallace easily could have transitioned into coaching, teaching or a variety of other pursuits.

Instead, he drifted into despair, falling into a spiral of drug addiction and homelessness that, a decade later, placed him under a bridge in New Orleans.

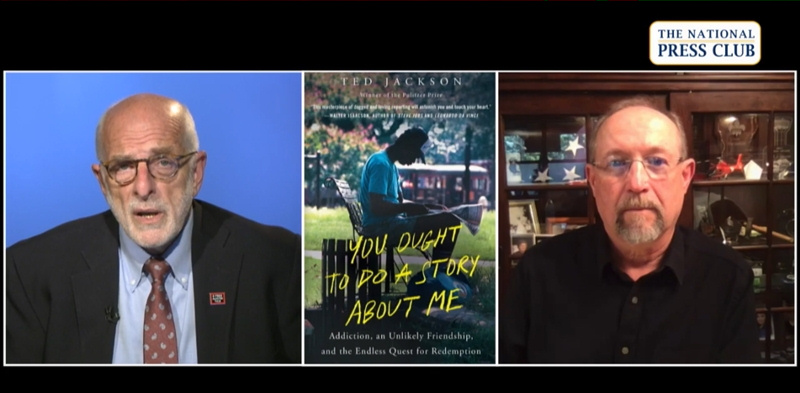

During a National Press Club virtual Headliners Book event Oct. 5, the gripping narrative came to life one more time.

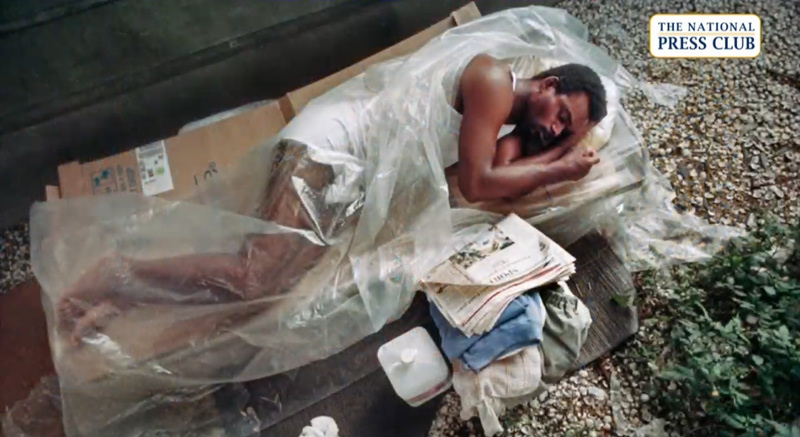

Ted Jackson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist at the Times-Picayune in New Orleans, just happened to see Wallace sleeping under that bridge one day, and, struck by the intentional neatness of Wallace’s nearby possessions, made a well-composed photograph.

Wallace’s journey — from NFL star to homeless drug addict — forms only part of the narrative of Jackson’s book, “You Ought To Do A Story About Me: Addiction, an Unlikely Friendship, and the Endless Quest for Redemption,” Jackson said during the Headliners Book event. The book was published in August.

He told viewers that his photo, which he figured would collect dust in a file, sparked a lifelong friendship that explored faith, mental health and the pressures on a talented athlete without a game to play.

It was also a continuing lesson for Jackson — who has spent his career capturing scenes of poverty and devastation, including the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 — on empathy between the photographer and the subject, he said.

The camera can be an “emotional barrier that allows you to pretend it’s not real,” as a photographer mulls over technical details like composition, light and movement, Jackson said.

Jackson’s experiences with Wallace, natural disasters and impoverished communities “kind of paralleled together to help me to really care about people I was photographing and not just treat them as subjects.”

The story that Wallace asserted Jackson ought to do ended up being one of a search for redemption, he said.

Leaving football stripped Wallace of his identity, Jackson said, and the NFL, at that time, had no programs in place to help its players adjust to life after the league. After his mother died, Wallace was in and out of drug rehabilitation facilities, dropping out of touch for years at a time.

Jackson’s photograph, which shows Wallace sleeping next to a Times-Picayune feature on retired NFL stars, prompted the league to institute programs for retired players almost “overnight,” Jackson said.

It also led to a turnaround in Wallace’s life.

Many years later, Wallace pulled out an envelope with the original photos from that day in 1990. Wallace told Jackson: “I have to look at these pictures every day to remind me that one bad step will send me right back there.”

Today, Wallace now lives in Louisiana, just 20 minutes away from Jackson at a facility that mentors ex-addicts.

“There’s a [Bible] verse that says if you don’t listen to the cry of the poor then you, too, will cry out one day,” Jackson said. “Those are verses that are easy to read in Sunday school, but when you live it, in a very dramatic way, they become very personal.”